The recent announcements by the governments of France and the U.K. that they have some (limited) readiness to “recognize” a Palestinian state change nothing– either regarding the genocide in Gaza or in the diplomacy over the Palestine Question more broadly. What they do do, however, is highlight once again the debate that has long simmered within the Palestinian-rights movement over whether the goal of the Palestinian movement should be a fully democratic one-state situation (‘solution’) or a two-state situation in which Palestinian and majority-Jewish Israeli states co-exist side-by-side in the land of historic (Mandate-era) Palestine.

But maybe now is a good time to re-examine another formula that’s been on the table for nearly 80 years now: that of, effectively, the three-state situation prescribed by the Partition Plan for Palestine as defined in the UN General Assembly’s Resolution 181 of November 1947?

That 1947 Partition Plan is, after all, the only authoritative and geographically delineated plan for governance in historic Palestine that carries the imprimatur of the UN and thereby its certificate of international legitimacy. And we should all care about international legitimacy, right?

In the 1947 Partition Plan the third (state-like) entity was planned to be an internationally governed corpus separatum encompassing the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem and some of the lands around them. That may have seemed like a good idea back in 1947, when states of “White”, Christian, European heritage still dominated the UN… But let’s leave the issue of the corpus separatum aside for now and focus instead on the rest of the UN’s 1947 map.

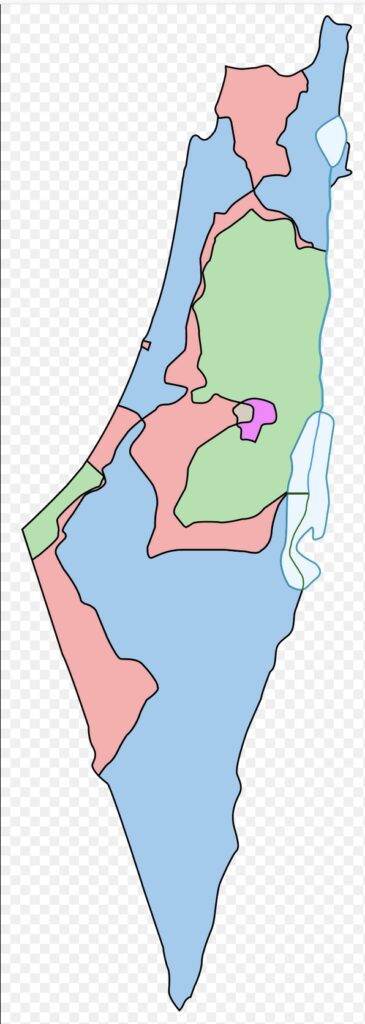

Look at it carefully. In the rendering here, the three white areas are the zones to which UNGA Resolution 181 of November 1947 gave formal recognition as constituting the Jewish state. Then, there are four areas, colored grey here, to which Res. 181 gave recognition as constituting the Arab state in Palestine. (One of them is very small: It is the area around the old city of Jaffa.) At two notable choke points– West of Latrun and South of Nazareth– these lines meet and cross at places at which contiguity for both the states could presumably be assured by bridges or under-passes…

The Partition Plan defined in Res. 181 was certainly a clunky arrangement! Even more crucially, in its very conception as a UN-imposed division of the Palestinian people’s ancestral lands, it radically violated any idea of the “sovereign self-determination of the world’s peoples” and many of the other fine precepts on which the then-new United Nations was based. (See strong, well-argued critiques of its illegitimacy, that are buttressed by plentiful factual evidence, here–the PDF of a powerful 1997 analysis by by Prof. Walid Khalidi– or here, or here.)

But however clunky and unethical it was, the 1947 Partition Plan remains the only authoritative ruling by the world body on where the two ethnically separated states in historical Palestine should be located.

Over the past 58 years, by contrast, nearly all the discussion within the “Western” discourse over how historic Palestine might be divided between an Arab and a Jewish state has fixated on the lines that existed immediately prior to the Arab-Israeli war of June 1967. The “two-state solution” in this discourse has generally been envisaged as involving an Israeli withdrawal only– at most– back to the lines of June 4, 1967.

Those pre-1967 lines had been defined in a series of UN-mediated Armistice Agreements concluded in late 1949 between “Israel” and its four Arab-state neighbors, all of which had (belatedly) sent military expeditions to support the beleaguered Palestinian units that struggled between 1947 and 1949 to resist the Zionist/Israeli forces’ harsh expansionism and campaigns of ethnic cleansing.

The lines in the Armistice Agreements were very different from those of the UN-endorsed 1947 Partition Plan.

This diagram (right) shows how the Armistice Agreements transformed the map. All the areas in red were parts of Palestine that the UN’s 1947 plan had allotted to the Arab state, that the Zionist/Israeli forces had seized during the fighting of 1947-49. The small grey area in the middle was the part of the Jerusalem corpus separatum that the Zionist/Israeli forces seized.

The British-officered Jordanian army was left in control only of the (green-colored) West Bank and (fuchsia-colored) West Jerusalem. The British-officered Egyptian army was left in control only of the (green) Gaza Strip.

The indigenous Palestinian resistance/defense militias had been sparse and poorly equipped at the beginning of the fighting that raged from 1947 through 1949, and by the end of the fighting they were in complete disarray and were never able to take part in any of the armistice negotiations that were sponsored, mediated, and supported by the UN.

Along the way, as we know, the Zionist/Israeli fighters did all they could to ethnically cleanse all the areas they controlled (both blue and red on this map) of their indigenous inhabitants. Scores of thousands of Palestinian Indigenes were pushed (‘concentrated’) into Gaza. Broadly similar, or even greater, numbers were pushed into the West Bank, Lebanon, and Syria.

In Israel’s 1949 Armistice Agreements with Lebanon and Syria, the lines of demarcation ran along the generally (though not completely) well defined international borders drawn in the early 1920s between Palestine and those two neighbors. As did most of the Armistice line between “Israel” and Egypt, and the southern portion of the line between “Israel” and Jordan. But the Armistice Agreement between Israel and Egypt stated specifically that that Armistice Demarcation Line was

delineated without prejudice to rights, claims and positions of either Party to the Armistice as regards ultimate settlement of the Palestine question.

And the Armistice Agreement between Israel and Jordan stated similarly that,

no provision of this Agreement shall in any way prejudice the rights, claims, and positions of either Party hereto in the peaceful settlement of the Palestine question…

A lot more can be said, of course, about the collapse of the Palestinian national leadership in that period and the fact that from 1948 until the founding of the PLO in 1964 there was no unified Palestinian national leadership. (I wrote about the Palestinian political developments of that era in my 1984 book The Palestinian Liberation Organisation: People, Power, and Politics.)

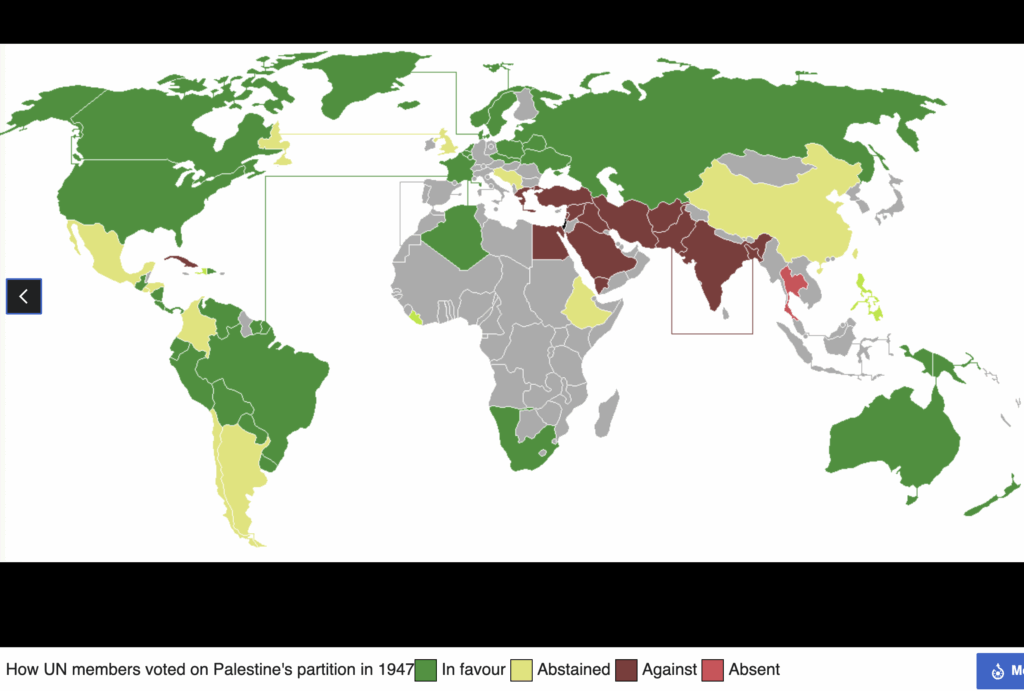

A lot could and should be said, too, about the international context in which the UN had adopted the 1947 Partition Plan for Palestine. This world map (click to enlarge) shows which states voted for the plan (green), which voted against (brown), and which abstained (yellow.)

Four things leap out of the map:

- Many states that are important members of today’s UN– especially those in Africa– were not represented in the UN in 1947 because they were still under colonial control. (The grey color here represents that. In this map, Algeria is colored green because it was still considered an integral part of France.)

- Those who supported the partition were the big White settler states, many South American settler states that labored under heavy U.S. influence– and the Soviet Union, which had longstanding ties to the Zionist movement, many of which survived in some form in post-Soviet Russia.

- Those who opposed it were a solid geographic bloc from Greece and Egypt eastward to India. (Jordan and Yemen did not have UN votes yet.)

- Those who abstained were an interesting bunch, including China, the UK, and Mexico.

The main point I want to make here, is that the (pre-June 1967) Armistice Lines have no particular standing in international law beyond being the ceasefire lines that arose from that one particular bout of fighting. If there is any set of borders for a two-state solution within historic Palestine that has international legitimacy, then those would be the lines of the 1947 Partition Plan. So any actor in the international community that seeks to work for a two-state outcome that has solid international legitimacy should surely be working for the withdrawal of Israeli sovereignty and settlers not just from the areas Israel has illegally occupied since 1967 but also from all the areas it seized and illegally occupied in 1947-49.

If Israelis and their supporters want to cling to their (morally problematic) goal of a Jewish-dominated state in Palestine, then the only even part-way solid basis in modern international law on which they can base that claim is the 1947 Partition Plan.

The whole corpus of international law is meanwhile quite clear that all Palestinians displaced from their ancestral homes and properties within pre-1947 Palestine have the right to return to those ancestral homes in peace, and to regain their lawful possession of those properties or, if they should so choose, to receive compensation for them in lieu of repossession. It is clear, too, that this “Right of Return” applies whether the governance formula within historic Palestine is that of one state, two states, or anything else.

The basic principles of the Right of Return were enunciated in two key UN declarations adopted on, respectively, December 10 and December 11 of 1948. The first of those was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which stated (Art. 13/2):

Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

The second was UNGA Resolution 194, adopted one day later, which stated (Art. 11) that the General Assembly,

Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible…

Also of direct relevance: international law is quite clear that people’s status and claims under the provisions regarding refugee rights are inheritable by their offspring and by succeeding generations.

Since 1967, as we know, successive Israeli governments of many (though ovet time, increasingly right-leaning) political stripes have worked hard to colonize East Jerusalem and the rest of the occupied West Bank, along with occupied Syrian Golan, while also enacting many other coercive measures to control and circumscribe the lives of those areas’ legitimate, Indigenous residents. The U.S.-dominated UN has seemed quite incapable of ending those numerous, very significant violations of international humanitarian law (as it has also been incapable of ending the even more serious assaults, atrocities, and actual genocide the Israeli authorities have committed in Gaza.) Throughout these decades since 1967, the diplomatic positioning of the United States toward the fundamentals of the Palestine Questions has also shifted considerably toward “allowing” for the idea that some of the large areas of the West Bank into which the Israeli government had implanted large batches of settlers might be incorporated into Israel under some form of the (always postponed) implementation of a “two-state solution.”

In 2017, Pres. Donald Trump broke with that longstanding– somewhat guarded and mendacious, but increasingly deeply pro-colonization– stance and announced that the United States now recognized a greatly expanded and unified Greater Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. In 2019, he gave similar recognition to Israel’s 30-year-old annexation of Golan.

No other significant country followed suit with either of those “recognitions,” both of which positioned Washington as being in direct conflict with the demands of international law.

In his four years in office, 2021-25, Pres. Joe Biden did not rescind either of those recognitions. They still stand as U.S. policyto this day.

In December 2020, the UNGA requested the UN’s highest judicial body, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to give an advisory opinion on,

the legal consequences arising from the ongoing violation by Israel of the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination, from its prolonged occupation, settlement and annexation of the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967…

It took the ICJ 3.5 years to confer on those questions. Finally, in July of last year, it issued a strong Advisory Opinion that concluded that:

- the State of Israel’s continued presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory is unlawful;

- the State of Israel is under an obligation to bring to an end its unlawful presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory as rapidly as possible;

- the State of Israel is under an obligation to cease immediately all new settlement activities, and to evacuate all settlers from the Occupied Palestinian Territory;

- the State of Israel has the obligation to make reparation for the damage caused to all the natural or legal persons concerned in the Occupied Palestinian Territory;

- all States are under an obligation not to recognize as legal the situation arising from the unlawful presence of the State of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory and not to render aid or assistance in maintaining the situation created by the continued presence of the State of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory;

- international organizations, including the United Nations, are under an obligation not to recognize as legal the situation arising from the unlawful presence of the State of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory; and

- the United Nations, and especially the General Assembly, which requested the opinion, and the Security Council, should consider the precise modalities and further action required to bring to an end as rapidly as possible the unlawful presence of the State of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.

The matter the ICJ was considering was, it should be noted, only the situation in the Palestinian territories “occupied since 1967”– and not those occupied since 1947-48. But this was an unequivocal and strong ruling and if a majority in the UNGA should wish to, they could seek to get its provisions extended also to the territories occupied since 1947-48. Certainly, the demarcation lines that existed in the 1949-67 period should not be unduly fetishized, at the expense of the greater (procedural) international legitimacy that underlay the lines defined in 1947.

The scene is now set for a clear, potential showdown over the diplomacy of the Palestine Question between the forces of international legitimacy, as (somewhat imperfectly) embodied in the ICJ advisory opinion of July 2024 and the clear and continued scofflawry of the U.S. government. At last year’s General Assembly session we tragically did not see this showdown come to a head. Shall we see it during this year’s pretty historic 80th annual session, which opens in New York on September 9?

Of course, a huge proportion of the attention of the global public is still– quite rightly– focused on the ever-unfolding horrors of Israel’s genocide in Gaza. It is of the utmost urgency that these horrors be speedily brought to a complete and sustainable end, and that plans for the very extensive rehabilitation and reconstruction that the Palestinians of Gaza (and the West Bank) so urgently need be implemented without delay.

But realistically, how can any of this happen so long as Israel and its closely involved partner-in-crime the United States are allowed by the world community to continue to monopolize any and all decisionmaking regarding the Palestine Question? And how can it happen so long as Israel is allowed to continue with its (now clearly judged-to-be-illegal) occupation of Gaza and other Palestinian lands?

To be continued…

The above essay is midway between being a freeform exploration of ideas , and a provocation. I realize there is a lot more to be written, to flesh out some of these ideas– and also, crucially, to give due consideration to plans to create the single democratic state that was historically the goal of many or most Palestinian nationalists. ~HC