As someone born in the early 1950s, I have never known a world without the United Nations. But by adopting Security Council Resolution 2803 (text) on November 17, the 15 states that sit on the UN’s most authoritative body, the Security Council, have now knowingly given a green light to the genocidal American-Israeli assault on Gaza, in clear violation of all the norms and values on which the UN was founded.

Thirteen of those states (including four Muslim-majority nations) voted for the U.S.-presented resolution. China and Russia, either of which could have blocked it by wielding a veto, chose not to do so. It seems that all those 15 states are prepared to rip up the entire international “system” of which the UN is the linchpin, and to let the world crumble into a stew of “might-makes-right” anarchy.

Craig Mokhiber, the 30-year veteran of the UN’s human-rights system who resigned his post in late October 2023 when he accused the UN of having failed to prevent Israel’s already-underway genocide in Gaza, published a powerful and well-documented piece on Resolution 2803 on Mondoweiss November 19. It clearly laid out the many ways in which Resolution 2803 violated longstanding UN norms, including those enshrined in its 1945 Charter.

In a discussion with Ali Abunimah on the EI Livestream yesterday, Mokhiber developed his critique even further. He noted that Resn. 2803 gives Pres. Trump the sole authority, via his position as head of the grotesquely mis-named “Board of Peace”, to do anything he wants regarding the administration of Gaza. Mokhiber’s comment: “It’s not even colonial, it’s King Leopold-esque.” (That recalled the fact that during the grossly genocidal period of “Belgian” rule over the Congo, 1885-1908, that whole vast territory was being administered as the personal property of Belgium’s King Leopold II.)

Mokhiber’s bottom line on what the UNSC vote means for the people of Gaza, and for the concept of the international rule of law more broadly, was grim indeed. (You can watch the whole of the conversation on the EI Livestream here, or read the transcript here, PDF.)

Two months ago, I had a very informative conversation with Amb. Chas W. Freeman, Jr. on “Gaza’s Genocide & Our Shifting World Order.” That was at about the time leaders from all round the world were gathering in New York to hold the 80th annual session of the UN General Assembly. Freeman said something then to the effect that the UN “may not be around forever.” I confess that back then I found that prediction pretty shocking. It’s true that in the course of my long career as a journalist, columnist, researcher, and writer, on numerous occasions I’ve reported on and worked hard to analyze incidents in which the UN has fallen very far short of its own norms and rules… But until recently, the organization always managed somehow to stumble along, with its reputation dented but its basic capacities and its idealistic worldview as an institution dedicated to “[saving] successive generations from the scourge of war” more or less intact. So what was different now? (I hope to press Freeman a lot more on this, at some point soon.)

The Security Council vote on Resn 2803 confirmed that Freeman’s prognosis looked very much to be on target.

If indeed the whole UN-led “world order” is going to continue crumbling over the weeks or months ahead, what then might humankind be left with?

Over the decades the UN has, as I noted above, suffered numerous serious (and often self-inflicted) injuries to its aspiration to provide global leadership that is collaborative, rules-respecting, and effective. One of the gravest of those injuries occurred on November 29, 1947, just two years after the General Assembly’s first session, when the GA adopted a Partition Plan for Palestine that flew in the face of all the UN’s previous commitments to help the populations previously governed under League of Nations “Mandates” speedily achieve self-government. That 1947 Plan (UNGA resolution 181) divided Palestine and established a Jewish State in a majority of its territory, though the country’s–mostly recently arrived)–body of Jewish settlers accounted for only one-third of the population.

See more about the grave injustices that flowed from the 1947Partition Plan, here.

The U.S., under Pres. Harry Truman had pushed very hard indeed for passage of the 1947 Partition Plan. Over the 78 years since then, the U.S. government has adopted various different approaches to working with United Nations in successive, grave international crises. In the Korea crisis of 1950-53, it was able– because of Moscow’s absence from the Security Council– to win explicit UNSC support and approval for an essentially American-led war effort. Other times, it just skirted around or avoided the whole question of UNSC approval, or pushed claims of ambiguous UN “approval” for U.S. military actions that went much further than most other UN members were comfortable with.

On Arab-Israeli diplomacy, different Republican administrations in Washington were twice happy to have the UN convene big Arab-Israeli “peace” conference: one in December 1973, and then another in October 1991. But on both occasions, after the UN held those big big public affairs the U.S. diplomats just proceeded to pursue their own diplomatic efforts unconstrained by any continuing UN supervision.

Regarding West Asian denuclearization efforts, in 2015 one U.S. administration was happy to bring the UN in as a co-sponsor of its JCPOA agreement with Iran. But then the next U.S. administration unilaterally withdrew from the JCPOA, and neither the UN nor any other body was able to prevent that or to to hold Washington accountable in any way.

So now, let me circle back to this question: If and when the UN’s power continues to crumble, what will the “family”of the world’s nations be left with?

The answer to this question falls into two main categories. One relates to the whole body of (supposedly binding) international treaties to which various different countries– including in many but far from all cases, the United States– are party.

These treaties are, in theory at least, not dependent at all on the United Nations for enforcement, but rather, on the actions of the individual states that are party to each one. So especially if and as the powers of the UN wane and crumble, we should demand that the states that are party to the relevant treaties should step up their enforcement efforts.

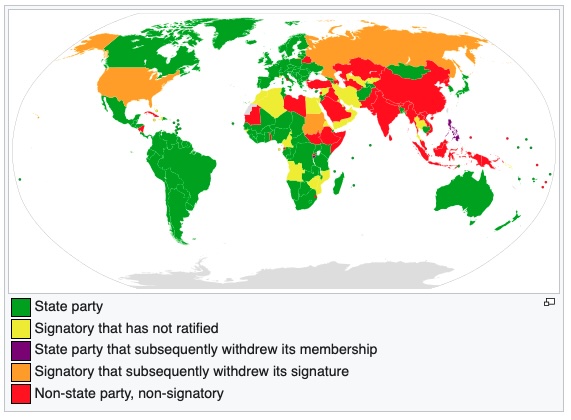

The most important of these treaties is, in the Palestinian context, the Rome Treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC), to which sadly the U.S. is not a party. Nor are Israel, Russia, China, or a handful of other states.

But for what it’s worth, the State of Palestine is party to the Rome Treaty. And most European states, and most other states round the world are also parties.

One key feature of the Rome Treaty is that it does have an enforcement mechanism, in that the individual states party to it are obligated to arrest persons for whom an arrest warrant has been issued. (As we know, though, many European states have failed to perform on that obligation, regarding the arrest warrants for Netanyahu and his colleagues.)

Other key treaties whose work becomes even more important as the UN crumbles are that venerable set of treaties known as the Geneva Conventions and the Hague Conventions. These treaties form the corpus of international humanitarian law (IHL), otherwise known as the Laws of War. The best-known of these treaties are the Geneva Conventions, which are commonly dated to 1949. But the versions agreed in 1949 were built on much earlier treaties dating as far back as 1864, when 12 European governments adopted the First Geneva Convention. The Geneva Conventions, which deal with the treatment of persons (both combatants and noncombatants) in times of war, have been expanded and updated considerably since then. The Hague Conventions meantime seek to restrict or outlaw various forms of weaponry deemed transgressively inhumane. One notable feature of both sets of treaties is that the body supervising their texts, the membership rolls of the states parties, and any efforts to ensure compliance has never been either the UN or before it, the League Nations. Instead, the depositary/supervisory body for both of them is the Geneva-based International Committee of the Red Cross, the ICRC, which is based in Switzerland and uses the professed (and often actual) political neutrality of that home-base to maintain working contacts with all the parties in any given conflict, in pursuit of its strictly non-political, purely humanitarian aims.

There are numerous other non-UN-tied international treaties that have significant bearing on different aspects of human safety and wellbeing. These include various broad-based arms control treaties, the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and its two derivative Conventions, the Genocide Convention, and many different treaties concluded between sets of states in the Global South or other parts of the world.

And then, in a different basket, there are the many directly UN-tied bodies whose operations may continue in some form even as the core nexus of UN power (in the UNSC) continues to decline: UNESCO, the WHO, the FAO, the ILO, and so on. Of these explicitly UN bodies, one crucial one is the International Court of Justice, ICJ, the very purpose of which is defined in Article 1 of its Statute as acting as “the principal judicial organ of the United Nations.” The ICJ’s origins, however, considerably predate the 1945 establishment of the UN. They go back to a precursor body called the “Permanent Court of International Justice” (PCIJ), which was established in 1922 and a relationship to the pre-WW2 “Leage of Nations” that was analogous to the ICJ’s relationship with the UN. in conjunction with the establishment of the League of Nations. A quick glance at what happened to the PCIJ as the League of Nations started to unravel in the 1930s, can thus give us some pointers on what might happen to the ICJ as the UN continues its current unraveling.

The League of Nations was never very effective. It had originally been the brainchild of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, who based it on the “14 Points” that he encunciated in a 1918 speech. But he was then quite unable to win support from Senate for his plan for the U.S. to join the League. That certainly delivered a major blow to the League’s effectiveness.

Over the 15 years that followed the League’s 1922 founding, it became clear it had many other weaknesses, too.

Nonetheless, during the 1930s, the PCIJ tried to remain active and relevant. It handled several cases, including issues related to international treaties, territorial disputes, and questions of international law. But– like the ICJ after it– the PCIJ lacked any enforcement mechanisms of its own.

Trouble was brewing in many parts of the world in that decade. And then there was World War 2…

After that war ended in 1945, the experiences and legal precedents that the PCIJ set during its existence were carried over to the ICJ, which probably made the establishment and operations of the ICJ more seamless and straighforward than they would otherwise have been.

Back in 2024, the ICJ delivered two very important rulings regarding Palestine. In the first, in January, it ruled in response to a claim that South Africa brought against the State of Israel that what Israel was doing in Gaza could “plausibly” turn out to be genocide, a policy that is outlawed under the 1950 Genocide Convention; and that Israel should therefore cease its pursuit of that policy, and other states should cease from aiding it do so. In the second ruling, which was an advisory opinion requested by the UN General Assembly, the court ruled in July 2024 that Israel’s continued military occupation over the lands its military had seized in 1967 was all completely illegal; that it should completely evacuate all its armed forces and its colonists from those lands; and pay reparations to Palestinians and others harmed by its lengthy occupation.

In regards to both those rulings, the ICJ completely lacked any enforcement mechanism of its own. The only way either of thembcould have had any tangible effect would have been if the UNSC had used the ruling as a basis for an authoritative resolution that would have created the UN’s own effective enforcement mechanism. That never happened. The UN has been hamstrung– primarily by the U.S. use of its veto, but also, as we have seen this week, by the deep reluctance of all the other international actors to decisively confront Washington on these matters– from doing anything to prevent or end Israel’s genocide and its illegal occupation of Palestine…

Just as, in the 1930s, the League of Nations failed to prevent Italy from invading and occupying Ethiopia and Libya, or Japan from occupying broad swathes of China and Korea, or Germany from occupying Czechoslovakia and other parts of Europe.

So maybe the existence of the ICJ and those two rulings its judges issued in 2024 will one day prove to have contributed to ending Israel’s genocide and occupation in Palestine? But that day seems very far off. And meantime, the genocide and Israel’s violent land seizures throughout Gaza, the West Bank, Syria, and Lebanon continue. The aspirations of the leaders who created the whole UN set-up back in 1945 now all lie in tatters.